When I launched my content marketing business as a side hustle in 2009, I had no intention of ever selling the business. Same when I launched The Write Life in 2013.

I started these businesses to earn a living on my own terms, and in the case of The Write Life, to own a platform where I could experiment with audience growth.

Years later, I ended up selling both businesses: the content agency as an acqui-hire in 2015, and The Write Life as an asset transfer in early 2021.

Now, as I launch another company, I’m approaching it with similar goals: I want my work to bring me joy, money and personal growth. Who knows if I’ll sell the next business; I might find it so enjoyable to run and/or so profitable that I want to stick with it in the long run.

But this time around, I know an acquisition might be on the horizon even if I don’t plan one from the early days. So it makes sense to do a few things from the beginning that position the business for a potential sale.

If you want to sell your business someday, the biggest variable is whether you’ve created a product or service that brings value to others. Quality is always the starting point.

But there are a few other things you can do from the beginning to make a business easier to sell later. You’ll notice second- and third-time founders covering these bases because they learned the importance of each one the first time around. Even if you didn’t do them from Day 1 of building your company, starting now will give you a leg up later.

If you want to sell your business down the line, here are four things you should do now to set yourself up for a successful future sale.

If you want to sell the company one day, create a brand that doesn’t completely revolve around you. Or at the very least, plan to pivot to that design down the line.

If the company’s brand is built on your reputation alone, another company might not be able to run it without you, which could make it challenging to sell. If you are the brand, it’s simply not worth as much without you.

Founders sometimes find creative ways to make this work, for example, by supporting a buyer during a transition period after a sale. But if the brand relies on you, it will likely be difficult to exit entirely.

Striking this balance can be challenging because brands with a face and personality tend to gain traction more quickly than brands that don’t share who’s behind them.

Especially in the early days of a business, customers tend to want to support the people behind the company more than the company itself. So one of the best ways to grow is to attach yourself and your personality to the business. Customers trust you, and because of that, they trust the brand.

I thought about this balance a lot with The Write Life. While I introduced myself as the founder on our About page to help the brand gain credibility and used my network to help the site find legs, the brand never revolved around me. Perhaps it would have grown faster if I’d been willing to put myself front and center, but I didn’t want to be known as an expert on freelance writing; I preferred to grow my career around the theme of building media businesses rather than that specific topic.

Simple tactics to apply here:

One of the biggest headaches for business owners when they go to sell is messy financials.

A buyer will want to see financial records for at least a year leading up to the sale, and possibly two or three years. If you keep your accounting clean from the beginning, you’ll avoid the massive chore of putting your books together or fixing mistakes — or worse, thinking your business is worth more than it really is.

One of the reasons this is a common challenge is because most business owners aren’t accountants. We run businesses because we enjoy the work, want autonomy and appreciate the financial benefits. But most of us don’t bring intimate knowledge of how to put together a Profit & Loss statement. In the best-case scenario, we learn the basics on the job and/or hire someone to help. Worst-case scenario, our financial books languish while we focus on growing the business.

I haven’t personally struggled with this challenge because my parents are accountants; my mom has served as my bookkeeper for as long as I can remember, and my dad has advised me on business strategy since I started my first business in 2009. But other founders have told me this is the number-one thing they wish they had done differently.

In non-accountant speak, here’s what I’d recommend:

👉 Track revenue, expenses and profit. If you have a lot of moving pieces, you’ll probably want a bookkeeper and software like QuickBooks. But at the beginning, tracking these numbers in a basic Google Sheet works just fine.

In addition to tracking money that comes in and out of the business, create a simple Profit & Loss statement (P&L) at the end of each month. This simple tool will help you understand how much money the business is making, spot financial trends over time, and identify opportunities for growth. Create a habit of looking at this sheet once a month to gauge progress.

👉 Keep business money separate from personal money. Even if you operate as a sole proprietor, where you are the business, keep these two buckets of money separate.

Open a separate bank account and credit card for your business, put all transactions through those accounts, and pay yourself by transferring money from those accounts into your personal accounts.

There are lots of reasons to do this, but for our purposes, keeping your business money separate makes it easier to track revenue, expenses and profit. It also sets you up for growth over time.

👉 Track this business separately from your other ventures. Most entrepreneurs have more than one project or company at any given time. You might work as a consultant while also growing the business you hope to sell one day.

For tax and legal purposes, it might work to have all of this business money reported in one bucket, depending on how your business is structured. But you should still track revenue, expenses and profit for the business you hope to sell separately from your other business activities, so you don’t have to tease them apart later.

Perhaps even more importantly, when you run multiple projects, it’s easy to make assumptions about which ones are profitable vs. eating cash. Those assumptions can lead to poor choices, for example, keeping a business alive that’s not making a healthy profit.

Tracking and understanding these basic metrics from the beginning will help you make good business decisions, while setting you up to easily share financial records with an interested buyer when it’s the right time. If you do this well, you’ll spend your months leading up to a sale figuring out how to maximize your sale price, rather than simply getting your books in decent shape.

Note: If you’re a freelancer without employees, I wrote an ebook with my accountant dad that covers all the money basics you need to know in easy-to-understand language: The Money Guide for Freelance Writers. It’s aimed at writers but the information is applicable for all freelancers.

While every company valuation is in the eye of the beholder, most online businesses sell for a multiple of their profit.

Online content businesses, for example, typically sell for a multiple of 3-4x annual net profit. So if your business profits $100,000 a year, you might look for a sale price of $400,000.

Lots of other metrics and factors come into play, but this is the core metric another company will likely use to value your business. That means the number-one thing you can do to increase your company value is to increase your profit.

This sounds obvious. Of course you’d do everything you can to bring in the most profit, because that’s what a business is about, right?

But there’s a tricky quandary that becomes apparent to every startup founder early in the journey: how to balance profit vs. investing money back into the business to support growth.

Maximizing profit in the short term might mean more money in your pocket at that moment. But if you invest business dollars back into the business to accelerate growth, you could have a more profitable or more valuable company down the line.

For The Write Life, for example, I reinvested most of our business dollars to maximize growth throughout my eight years of running the site. I could afford to do this because I wasn’t relying on the site for income; it was always a side project. This strategy is a big part of why the site grew to 460,000 monthly pageviews.

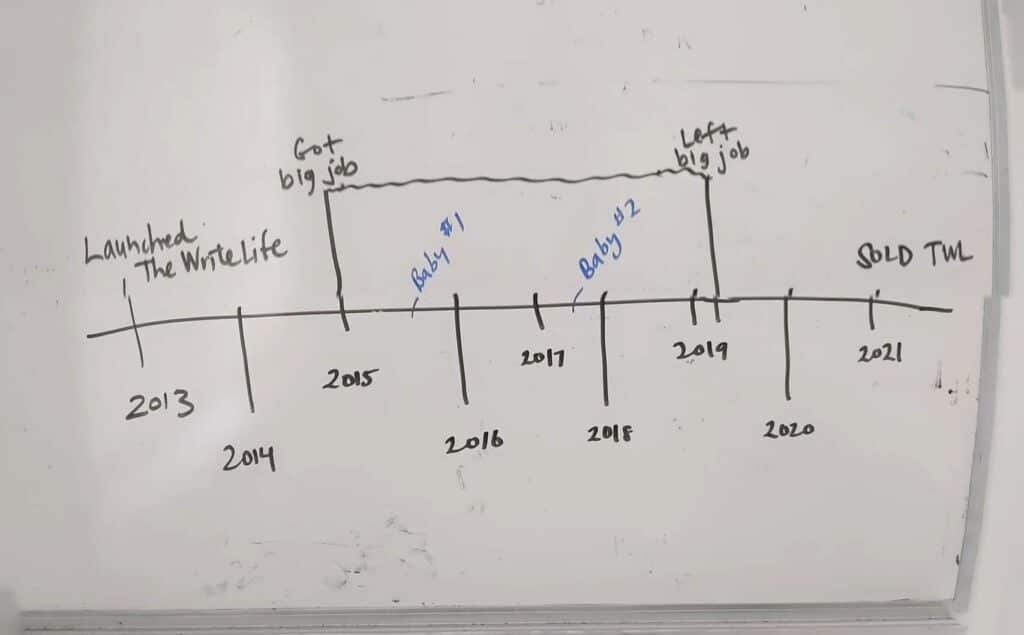

I also took this approach out of necessity. I was focused on another startup and my young family during several of The Write Life’s core years, so I spent money to keep growing the audience even when I couldn’t devote any personal time to the business.

Here’s a messy timeline that illustrates that:

Much of my own personal experience with growing companies has been about reinvesting heavily to accelerate growth. But my thinking has evolved here over the years, and for this next company, I want to push myself harder to minimize expenses and increase profit from the beginning as a way to force efficiency.

If you want a resource for thinking through this, I recommend Mike Michalowicz’s book, Profit First.

Your approach to profit can morph over the course of your company lifecycle; you can take one strategy at the beginning based on your own personal income needs and the needs of the business, and shift to another strategy later.

But even if you optimize for growth initially, plan to optimize for profit in the year or two before you sell the business.

This can be tricky because we can’t always anticipate the timing of our desire to sell or when an offer might come our way. But if you do spot a possible sale on the horizon, look for ways to increase revenue and cut expenses, effectively increasing profit, to maximize your sale price.

In addition to the brand being more than you, your company’s operations should also be bigger than you.

Can the company deliver on its promise without you doing all the work? Are your duties systemized and documented so someone else could take them over and keep the business running smoothly?

Most founders do much of the work themselves, at least initially. I see benefits to starting this way, at least for tasks you’re semi-qualified to do or can figure out, because experiencing them yourself can help you see what’s challenging, how long tasks should take, how to make tasks easier, how to create systems around tasks, etc.

But over time, if you want to position your company for an acquisition, your business must be able to run without you. This involves two parts:

While people can make or break the business, in my opinion, systems are more important.

If you build good systems and document them well, you can find qualified people to do the work.

But it doesn’t work the other way around: If you have good people but no systems for them to follow, they might falter. Those people are then critical to your business; if they leave for whatever reason, you won’t have your systems to fall back on.

As a founder, you don’t have to build all the systems yourself. If you’re not sure exactly how a task should be turned into an efficient process, hire an expert in that field and ask them to build the system and document how they do it so someone else could do it, too.

One challenge of documenting systems at a small, agile startup is that things change constantly. How you do the work will change as you figure out better ways to work and take advantage of new opportunities. That’s the beauty of a small shop; you can adapt quickly in whatever way benefits you and the business.

But this means process documentation is out of date almost as soon as it’s been written. It’s most important to update it before you bring on new hires, so they have accurate documentation to follow, and before you sell the company, so the buyer has up-to-date guides.

If your process documentation is out of date at other times, that’s ok. In fact, it’s normal. But don’t use that as an excuse to not create it at all. Having documentation that’s not perfect is better than having no documentation at all. It will guide you as you grow your business and your team, and minimize work when it comes time to sell.

A great resource for learning about the importance of systems and how to create them is John Warrillow’s book, Built to Sell: Creating a Business That Can Thrive Without You.

The good news is that you don’t have to do all of these things at once. Take your time putting them in place, at a pace that’s manageable for you.

When you first start a business, you have so much on your plate. Your most important task is to ensure you have a product or service that offers value, something customers will pay for. Once you’ve validated that, it makes sense to look to the future.

If, however, you’re beyond the early stages and see a path to an acquisition, work on these items as soon as you can. They all take time, and a buyer will want to review at least a year’s worth of data for a valuation.

If you take steps to optimize for profit, for example, you’ll want at least a year’s worth of maximum-profit P&Ls to get the best possible sale price. Likewise, putting systems and good people in place so the business can run without you requires trial and error over time. You probably won’t do it well if you rush it.

And what if you follow this advice and never have an opportunity to sell your business?

Congratulations are still in order, because if you’ve worked on each of the items on this list, you’ve likely made your business more scalable, more efficient and more profitable. And probably more enjoyable — and less stressful — too.

👉 If you’ve read this far, you might enjoy my newest company: They Got Acquired.