In my work growing content teams, which includes maintaining a vast network of freelancers and helping startups hire writers, this is the question I get asked more than any other:

How much should I pay a writer?

I wish I could respond immediately with a number: “$25 an hour!” Or “$80,000 a year!” But as with every profession, compensation varies widely based on lots of factors. So to arrive at an answer to your question, I have to first ask some other questions.

Questions like, what topic are they writing about? Are they early-career or experienced? What type of writing are they producing? And more.

In this post, we’ll cover the factors that affect writer pay, plus other details that will help you figure out how to compensate your writers.

Here’s what’s included below (click to each section to skip right to it):

To get us started, here’s a decision tree that shows how I think about how much to pay a freelance writer for a specific deliverable: a blog post.

We’ll review all the decision points in this flow chart — for example, what qualifies as a highly specialized topic — later in this post.

This chart assumes something important: that you’re hiring an experienced writer. That’s someone who can produce clean copy that doesn’t require a ton of edits. If you hire an inexperienced writer whose work requires a lot of editing, you will probably pay less. (At least in writing costs. You’ll probably pay more in editing costs. I dig into that more below.)

Most hiring leads want a writer who produces great work on their own. If that’s the case, and if you’re looking to hire a freelancer (not an in-house staff writer), this decision tree might be useful. If those specifics don’t fit your situation, use this flow chart as an example to understand some of the factors that affect compensation for writers.

Here’s how to figure out how much to pay a writer for a blog post:

Hiring writers is hard. Most leaders underestimate just how hard it is. But while finding high-quality writers is challenging, figuring out what to pay them doesn’t have to be.

Whether you’re looking to hire a full-time staff writer or a freelance writer, here are the factors you should consider when figuring out how to compensate that person:

Let’s review each one in detail.

Are you looking for an experienced writer or a writer who’s early in their career? Someone who’s been writing professionally for years, or who is new to the industry?

Some clients I work with know they want an experienced writer right off the bat. Others are open to an early-career writer with growth potential.

Here’s a mistake I see a lot of companies make: saying they want an early-career writer, usually with the goal of keeping expenses low, but expecting the work quality to match that of an experienced writer. In other words, they hope to hire someone great on the cheap.

Sometimes you’ll get lucky with an early-career writer. But usually, skill comes with experience, and experience costs money.

Writers with years of experience typically produce better work than new writers who have a lot to learn. Their copy is cleaner and reads more smoothly. They require less editing and hand-holding than their up-and-coming counterparts.

If you have an in-house content lead (typically an editor) willing to teach and guide early-career writers, it can make sense to hire inexperienced writers and help them find their legs. After a year of training, you might have a high-caliber writer at a lower-than-market rate. This is incredibly satisfying when it works out; some new grads I began working with years ago are now the best writers I know.

But it only works if you have experienced content creators who are a few steps ahead to guide inexperienced hires. If you don’t have an editor in-house who has time to lead this training, the work product might fall short.

You can get a sense of a writer’s experience by reviewing their LinkedIn profile, resume or portfolio; if writers have clips from respected publications, that’s a sign that they bring experience.

However, not all writers who have years of experience or clips in respected publications produce high-quality work.

Don’t assume that just because someone has written for a well-known publication, they’ll produce great work for you. I made this mistake years ago and learned my lesson. Keep in mind that an editor likely polished each of their stories before they were published, and it’s impossible to know how much of the story was written by the editor vs. the writer.

Even if you’re impressed by their portfolio, vet experienced candidates through a writing trial. You might be surprised by their unedited copy, and it’s much better to know that up front.

Leaders who don’t work in content sometimes think, hey, a writer’s a writer! But writers have different areas of expertise, just like lawyers specialize in different types of law and doctors specialize in different types of medicine.

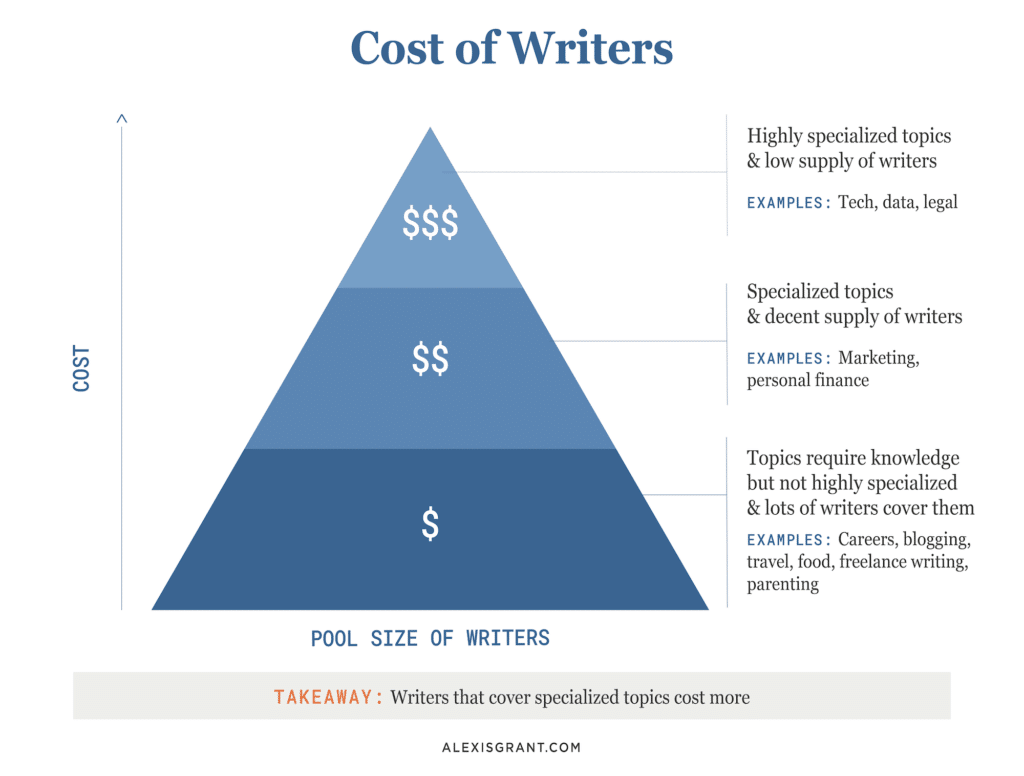

It costs more to hire a writer in a specialized field than it does to hire one who writes about common topics.

Every writer has some specialization, some niche topics they write about. The question is, how specialized is the topic itself? And how challenging is it to find writers who can cover that topic well?

This is partly about paying a writer for their expertise, and partly about supply and demand.

I think of topics as falling into two buckets:

This includes topics like technical writing, legal writing and writing about data. It’s challenging to find writers who specialize in these topics because there aren’t that many of them.

Topics like personal finance and marketing also require some specialized knowledge, but there are more writers who cover these topics, which drives cost down slightly.

Topics like careers, travel, parenting and food fall into this bucket, as do blogging and freelance writing. You still need specific knowledge to write about these topics well, but that knowledge is more common and a lot of writers cover these topics.

That doesn’t mean you can pick any writer and they’ll do a great job — it just means you’ll have more options to choose from. And if you’re looking for a specific niche within one of those topics, it might be more challenging to find the right person, which can drive the price up.

Here’s a pyramid chart to help you visualize how the topic of the writing can affect cost when hiring writers:

.

While topic is one way to specialize, some writers also specialize based on the type of writing. Think of this as their deliverable, or what they’ll produce for your company.

Like with topics, some types of writing are more common than others. A few examples:

Blog posts are common; a lot of writers know how to write them, so they cost less than other types of writing.

Fewer writers specialize in case studies and sales pages, so those can cost more.

Does the writing assignment rely solely on the writer’s personal experience and/or scouring the web for information to include?

Or do you need a writer who’s also a reporter? Someone who will dig up original information by interviewing people, looking through records, and attending events?

It takes less effort to write a piece that’s based on personal experience, advice (aka “10 Things I Learned”) and information gathered around the web.

It’s more time-consuming and requires more skill to conduct original reporting and include information that hasn’t been covered elsewhere.

Generally speaking, original reporting costs more. This isn’t a hard-and-fast rule; you might pay top rates for an advice piece based on personal experience if that experience is specialized or if the writer has a unique perspective. But interviewing and reporting are specialized skills that writers develop over time and that help your end product stand out from competitors — which may be worth paying for.

This factor applies more to hiring for project-based or freelance work than to hiring a full-time staffer.

Are you assigning a blog post of up to 1,500 words? A long blog post of 2,500 words? Or an even longer project?

Word count is an outdated way to calculate compensation, as I’ll explain below. But length is still a factor that affects how much you’ll pay.

Do you need the writer to add a layer of SEO to everything they write? Are they expected to do their own keyword research around the piece, or will you provide keywords?

It’s relatively easy to find a writer who understands the basics of SEO, but harder to find a writer who has been properly trained in optimization strategy (i.e., they can identify target keywords on their own) or who has worked alongside an SEO specialist.

If they’ve done the latter and SEO is important to you, that’s worth paying for.

Needing a writer with a specialization is normal. If you don’t look for a writer with a specialization, you’re probably doing something wrong.

Yet some companies add an extra layer here, and this is what I call a “unicorn skill.” A unicorn skill is a skill the writer needs to bring in addition to their ability to write authoritatively about the topic.

For example, a company came to me recently for consulting support to find a writer who can write knowledgeably about spreadsheets — and also create spreadsheet templates. It’s certainly possible to find that unicorn, but it will take more work than simply finding a writer with topic expertise, and that unicorn skill will likely add to the cost of hiring the writer.

In essence, this company wants to hire a writer and a spreadsheet template maker, all in one. They’re already hiring a writer to cover a highly specialized topic — spreadsheets and data — so when you tack on this unicorn skill, I’d expect to pay a pretty penny. But for the company, finding the right person for this role will be worth it.

Before you can answer how much to pay, you have to figure out how you want to pay.

Should you compensate with a salary, per-word rate, hourly rate or project rate?

Here’s what each of those options look like in the writing world, and which one I recommend most.

The cost to hire a staff writer for a full-time role is across the board, based on the factors outlined above, plus benefits and more.

You could hire an early-career writer for $40,000 a year or an experienced technical writer for $110,000 a year. And yes, experienced writers in hard-to-find niches can absolutely command a six-figure salary. The spreadsheet writer/template maker above is a good example.

If you know what type of writer you want to hire, PayScale and Glassdoor offer average salaries for various roles.

Paying by the word is an antiquated compensation structure that is primarily used by old-school print publications or publications that serve traditional industries.

However, it’s good to understand this structure because a writer with years or decades of experience might use a per-word calculation as one data point in determining the value of the work, even if you don’t pay by the word.

I believe paying per word incentivizes the writer poorly. It encourages the writer to write more, when a sign of good writing is actually writing less.

Plus, on the web, unlike in print publications, there’s no limit to how many words you can publish. The goal should be to cover the topic well, using however many words are required, not to aim for a specific word count.

This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t provide a word count expectation when giving a writer an assignment. It’s helpful to identify a target word count up front to set expectations for both the writer and the assigning editor. But rather than say that this piece needs to be X words (like editors used to do when that’s how many words would fit on a magazine page), offer a large range.

For example, assign a blog post that’s between 1,200 and 1,800 words, or between 1,800 and2,500 words. And let the writer know you value the quality of the post over heavy word count, so they put their effort in the right place.

Per-word rates range from 5 cents a word for content mills to $1 a word (or even more) for niche publications. If you think in project rates (which I’ll explain below), that works out to $50 for a 1,000-word piece (a poor rate) vs. $1,000 for a 1,000-word piece (well paid).

The Editorial Freelancers Association lays out per-word and per-hour rates for different types of writers in this chart.

Some companies pay writers by the hour. In my opinion, this arrangement doesn’t usually work out for anyone, because like the per-word rate, it incentivizes the wrong thing. When you pay someone by the hour, you incentivize them to work slowly, rather than efficiently.

If you really dig deep on what a company cares about, it’s not how long it takes you to do the work. It’s how well you do the work, or the quality of the final work product.

Paying by the hour penalizes writers for getting better at their job. If they become more efficient over time, they get paid less. If their years of experience allow them to write well quickly, they get paid less. In both of those examples, they should actually be paid more.

There are a few exceptions, instances when it does make sense to pay per hour. For example, at The Write Life, we pay a writer to update previously published posts that we want to republish with accurate information. Some of the posts are short, and some are long. Some barely need any edits, while others need total overhauls. It’s challenging to offer a project rate (we’ll talk about those next) for these types of updates without mapping out a new scope for each post, so instead we pay an hourly rate. That way, the writer is compensated well whether they spend a few minutes or a few hours updating the post, and we don’t have to agree on a project rate for every post based on how much work it involves.

You might also pay an hourly rate when you first begin working with a writer, if you and the writer need time to figure out the scope of recurring work. Once you know how much effort it will take, you can agree on a project rate going forward.

Hourly rates for writers vary widely, but I’d expect them to fall between $15 and $40. Those rates are on the lower end of the spectrum because most experienced writers won’t accept hourly projects — something to keep in mind during your hiring process.

Paying a project rate is the best way to compensate freelance writers, so long as it’s a fit for the work you need completed.

Agree on a project or post scope (length, what it will cover, and any other expectation-setting details), and pay a rate for the completed work. Be sure to specify that it includes a round or two of edits, in which the writer makes changes you request.

With this arrangement, the writer benefits from their efficiency, and the hiring manager knows how much the work will cost them no matter how much time the writer spends on it.

For a blog post of up to 1,500 words, I’d expect to pay an experienced writer around $150-$300. Sometimes more, sometimes less; it depends on the topic, length and SEO. The flow chart at the top of this post maps out this decision process in detail.

For a blog post of about 2,000 words, I’d expect to pay an experienced writer around $250-$400. Again, sometimes more, sometimes less, depending on topic, length and SEO.

If you’re commissioning a package of several blog posts or paying a recurring project rate each month, you might be able to negotiate a slightly lower rate in return for the promise of ongoing work. While most freelance writers enjoy the variety of their work, they tend to crave income stability, so if you can provide that, it’s a win-win.

Writing is often under-valued. Why pay good money for a writer when anyone can write, right?

Wrong.

Anyone can write, but few people can write well, in a way that will help your company reach its goals.

Here’s the hard truth: Content is expensive to create. But developers are expensive, too. So are sales employees. If you’re willing to pay well for other roles, push yourself to value writers in the same way.

Whenever I work with freelance writers, I aim to be their best client, and that includes paying them well.

Here are three reasons it benefits you to pay writers well.

This might feel obvious, but it’s so important and sometimes overlooked. Your content will be better if you hire a great writer.

High-quality content translates into value in so many ways:

The list goes on and on. There is so much value in paying more. And when we’re talking about blog posts specifically, paying just $100 more per post could push your content into the next league.

Yes, this means adjusting your budget. But consider the return on your investment, and you’ll see it’s worth it.

Writers with less experience produce copy that needs more edits, requiring more time from your editor. And here’s the rub: editors usually cost more than writers.

You could save $200 on a project by hiring a cheaper writer, then spend twice that on the editor who needs longer to whip the writing into shape.

You’ll benefit from a solid editor no matter how good your writers are, but that editing will be less time-consuming and therefore cheaper when the writers submit high-quality drafts.

When you pay well, writers will want to keep working for you. This is largely a financial incentive, but it’s also emotional: paying writers well makes them feel valued. And that matters.

When you pay well, your writers will turn down work from other clients when time is tight so they can work with you instead.

This is huge from both money-saving and time-saving perspectives. When you have writers you can rely on, you’ll spend less time looking for and training new writers, which can be time-consuming, energy-draining and expensive. You’ll also be able to deliver on challenging or quick-turnaround projects because you’ll have an eager workforce by your side.

In my experience, this is one of the most important reasons for paying writers a little more than they’d get paid elsewhere. When you treat writers well, they will be loyal to you.

With all of this in mind, this last section — do writers ever write for free? — might feel contradictory.

Leaders who want to hire a writer usually expect to pay money for the work. However, some blogs still rely on contributions from writers who aren’t compensated in cash, so this topic is worth covering.

At some of the media properties I’ve grown, we’ve had writers contribute “for free.” I put that in quotes because it wasn’t really free: Contributors were compensated in back-links rather than money.

Now, before you get up in arms about these brands taking advantage of writers, consider this: If it’s monetized well, a good back-link can be worth more than a writer would earn for writing the post itself. As a writer myself, I’ve made this trade-off dozens, maybe hundreds, of times over the years, knowing a strong back-link could send eyes and buyers to my website, and tell Google to send people to my website, too.

As a quick example, I wrote a post for Mashable for free in 2011, then went on to earn tens of thousands of dollars by selling a guide on the same topic. People found my guide directly through my link in the post, and because Google ranked my site high in search results, which was partly a result of the Mashable link.

Compensating via “exposure” gets a bad rap, because some publications have used it as an excuse to pay writers poorly or not at all. And some writers do fall into the trap of only writing for exposure and not having a way to monetize those eyeballs.

You can probably tell from this post that I believe in paying writers well. I also believe there are times when it’s appropriate and mutually beneficial to compensate via a link instead.

Web traffic, credibility and back-links are all forms of currency. When a writer or organization needs that currency and you can help them earn it without spending cash, the door is open for a win-win.

Now, this game has changed in the last few years; the landscape looks different than when I got that link at Mashable a decade ago. Because there’s so much content noise online and it’s far more challenging to rank at the top of Google and gain traction on social media, guest posts simply don’t carry the weight they used to. The author usually doesn’t see as much return on their effort, so that non-monetary currency isn’t as valuable.

Other factors are at play, too. For example, years ago, several media properties I ran had a policy that allowed contributors to either get paid for their work or link to their website. This helped us hit our content publishing goals while keeping costs down and still paying most high-quality writers for their work.

But in the last few years, as credibility has become more important on the web and Google’s algorithm has evolved, it has become increasingly important to showcase the expertise of the writer within the post. One effective way to do that is to have the writer explain in the introduction why they’re qualified to write the post and link to a site that further showcases that credibility.

For example, in this post on how to become a grant writer, the author explains in the introduction that she runs a grant-writing company that serves organizations around the world. She also links to that organization. A win for her, a win for the reader, and a win for us.

For this reason, a policy whereby writers either get paid or get a link in their post doesn’t really work anymore.

Plus, most writers who want to contribute in exchange for a link nowadays tend to produce lower-quality work than professional writers who earn a living from their writing. The post might be overly promotional or simply not helpful for the audience. Guest bloggers also typically require far more editing, which takes time and energy from your editor and costs money in the form of editor hours.

For this reason, I typically recommend having a team of paid writers you can rely on for high-quality work, then sprinkling in the occasional guest contributor who might be satisfied with a back-link as compensation. Guest bloggers can add variety in perspective, but I don’t recommend relying on free work as your foundation.

Need a freelance writer and not sure how to find them?

Here’s a list of websites and communities where you might look to find and hire a freelance writer.

Remember: You don’t want a general writer. You want a writer who specializes in your topic.

So when you put your feelers out, don’t say you’re looking for a writer. Say you’re looking for a writer who’s intimately familiar with your niche: a parenting writer, an ed-tech reporter, a personal finance writer with experience covering cryptocurrency developments.

And when you find the right writer, show them you value them and their work by paying them well.

Many of the thoughts you lay out here are accurate, but the rate scale you share is misleading. These lowball rates create a skewed reality for publications hiring writers and only serve to try to reduce rates for those of us who actually make a good living freelancing. To get a clearer picture of what is actually being paid/charged in today’s marketplace, I encourage you to do a survey that accounts for expertise, experience, and location in addition to the metrics you specify in your flowchart above. Once you do that, I think you’ll quickly realize how out of touch those rates are in today’s freelancer world.

Pretty disappointed in your numbers. $250 for a specialized writer? That’s low and doesn’t account for writing and running a business. I feel like you need to do some better research on this.

Alexis, as always, thank you for being so transparent and for the user-friendly infographic.

And in response to the previous comments… Whether some writers ‘should’ be paid more for ‘some’ articles is not so much the point here – this is not a publication rate table for high end writers at The NY Times.

My interpretation of the point is that it’s about coming up with a strategy around what you pay, and knowing what rates you need to pay to achieve what you need to achieve.

Alexis, you’ve learned from years of experience that this table gets you the results you need, and (as both a writer and an employer of writers, depending on the circumstances), I appreciate that you took the time and shared honestly. Thanks!